In Atlanta, the BeltLine Approaches Climate Change by Design

I started this post while visiting Atlanta several weeks ago, but benched it after we returned from our trip. After spending a week in humid, Elsa-stormy Atlanta weather, I was eager to return home to cooler weather. Unfortunately, we were greeted with our second heatwave in 30 days. While it was nothing close to the heatwave that passed through the PNW last month, it got me thinking about the impact of increased average temperatures in cities, urban heat islands, and the impact of decades-old urban design across socioeconomic lines. And although I typically turn to technology and innovation for solutions to dig us out of the climate crisis, it’s often as simple as looking at the ground beneath our feet for the answer.

Hello from Atlanta 👋

Our week-long trip to ATL marks the first time Tammy and I have been on a plane since the Covid-19 pandemic began in 2020. Altogether, the experience of flying hasn't felt overwhelmingly foreign or stressful. Yes, there are the anticipated levels of heightened germaphobia and a general distrust of public space hygiene, but overall our early morning pre-flight experience was quick, organized, and completely masked. The SFO airport was plastered with signage signaling masks on at all times, which I would say nearly everyone obeyed in the early hours of 5-6 am. Landing in ATL, the experience was more of the same — strict mask signage, people observing distancing as best they could before a quick return to masklessness for once we stepped through the airport doors into a humid 80 degree Atlanta summer afternoon.

This is my third time in Atlanta in the last 10 years and each time I've grown to appreciate the city a little bit more. Although I'm not too familiar with Atlanta's urban design or its climate change commitments, I do know that over the three times I've visited the city, I've learned to love and appreciate the BeltLine.

Greenwood Ave entrance to the BeltLine

An installation for VietnamBlackSoldiersPortraitProject.com

Direct access to the BeltLine from Ponce City Market

A cyclist rides on the BeltLine outside of Ponce City Market

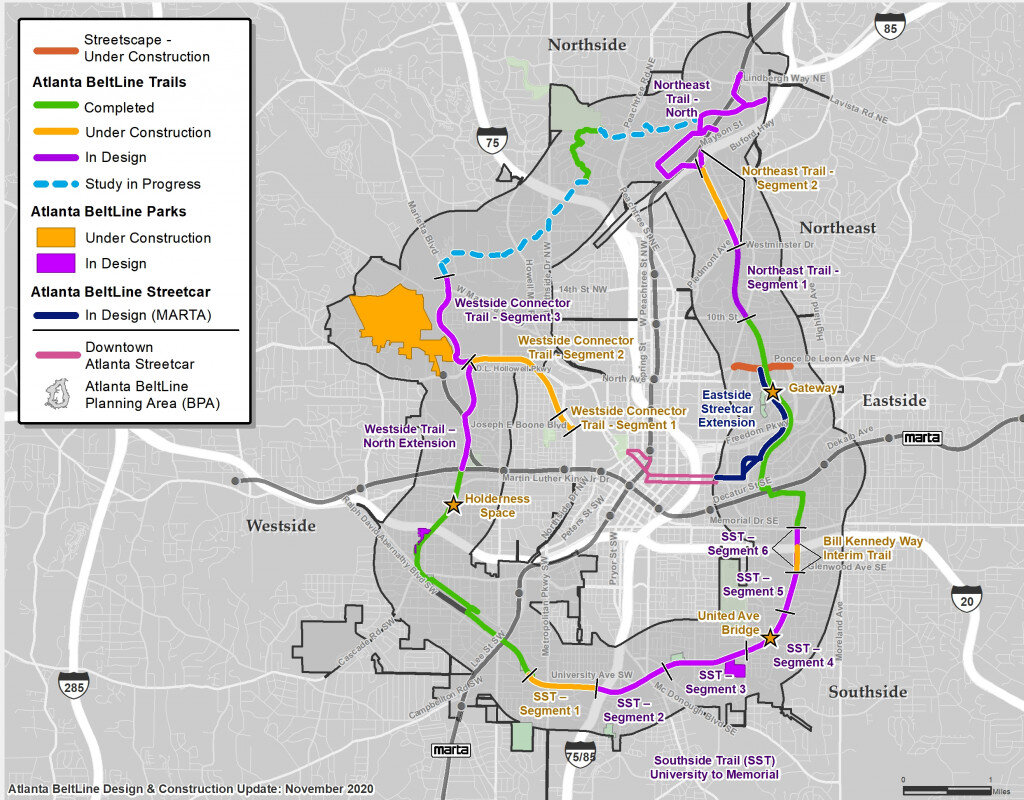

The BeltLine began as master's thesis by Georgia Tech student Ryan Gravel and has evolved into a multi-year program that has received millions of federal grant dollars and covers 22 miles of converted railway that are now pedestrian walkways, bicycle lanes, and a home to urban artwork. The project connects major neighborhoods throughout Atlanta's core — an intentional design that focuses on blurring the line between low-income and wealthy neighborhoods through common access to safe, accessible green space and improved walkability.

Not only does the BeltLine aim to revitalize unused and abandoned railways, but this rails-to-trails initiative is paving the way for a stronger relationship between people and their built and natural environments. The public greenways create common areas that protect people from the car-centric streets and surrounding highways while introducing more greenery which actively reduces the impact of urban heat islands that are known to disproportionately impact low-income neighborhoods and communities of color.

Projects like New York's Highline, Atlanta's BeltLine, and dozens more create a compelling case for inclusive, equitable, and restorative urban design. While the key projects metrics alone paint a positive picture (including more green jobs, more affordable housing, acres of new green space, and miles of improved streetscapes), it doesn’t account for the intrinsic impact of sustainable and measured urban design on the happiness of cities, reduction in carbon-intensive transit behaviors, or the positive impact on climate justice.

While technology is a clear driver for many of the decisions and opinions I hold on decarbonization, sequestration, and many more drawdown solutions, urban design is an accessible and proven solution that has been staring policymakers in the face for centuries. If technology, machine learning, and predictive scenario mapping can help us identify regions within cities that are prime candidates for public green space, then the anecdotal evidence from projects like Atlanta's BeltLine can drive home the message that oftentimes the obvious solution is to put more nature in our cities.