Why a Three-Pronged Approach Will Create Resilient Cities

When we moved into our new home a few years ago, we had the rare opportunity to shop for new furniture. The bed frame donated from my mom, my modular Lovesac sectional that looked more like college-aged furniture, and the mismatched rustic dining table were all either sold or given away.

I'm not going to lie and say it was a 100% fun process selecting the new pieces of furniture. In fact, it took months to finally settle on our bed frame, couch, and dining table. To this day, we're still trying to find furniture for the dead spaces — something functional that matches the aesthetic of our house, but meets a level of uniqueness.

If this sounds complicated, it's because it is. And remember, this is only furniture.

I'm describing furniture to set the scene for the discussion around the City of the Future — the sometimes detailed, but often nebulous concept that takes many forms.

Now, when you step out our front door and walk 10 steps down the sidewalk and face our neighbor's home, you'll see a similar image — a Tudor-style 12:12 pitched roof, large front window, stucco walls, and a modest front yard. But once you walk inside their home, the aesthetic is night and day. Compared to our white-to-neutral color palette and open floor plan, each space of their home is filled with a different bright color, intentionally separated by a traditional closed floor plan. We have a backyard filled with grass, planters, and a meager seating area, while they have a treehouse, hot tub, and ample seating for large family gatherings. But while each home looks and flows differently, they both accomplish their job — creating a comfortable, safe, clean, and functional living space for the people in it.

So, when I began researching urban design to learn more about our cities' impact on climate change, I watched the same pattern emerge — even though we all, as global citizens, want healthy, safe, and prosperous cities, we approach it in the ways that we're trained to see our environments: as urban planners, futurists, architects, agencies, financial organizations, technologists, or policymakers.

I explored many concepts and divided the approaches into 3 core categories:

1. People-first

Cities aren't buildings, they're people. - Randy Komisar, Kleiner Perkins

It's true. I believe that the city is humanity's most important and significant invention. Cities have the ability to bring people together and create ecosystems where they can cooperate, collaborate, and thrive. Cities are a source of endless innovation, born from diversity, and driven by our collective ambitions and needs.

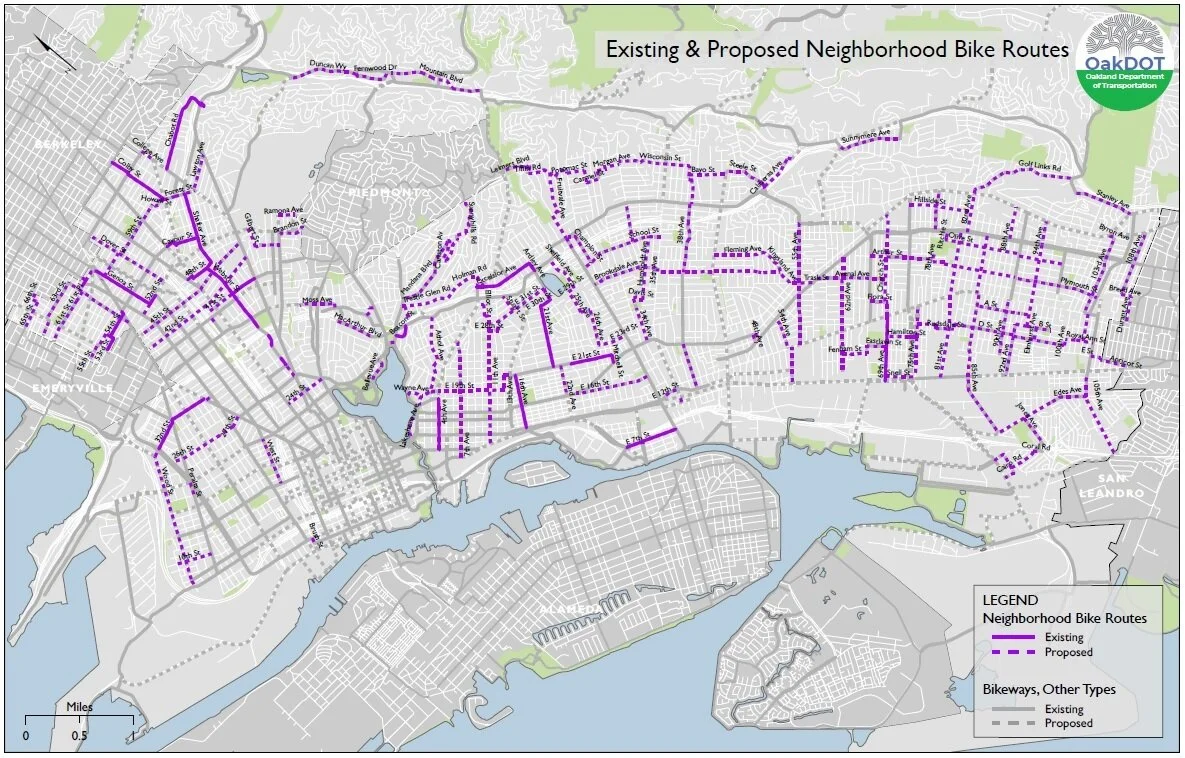

This people-first approach to urban planning is a core value at Gehl, IKEA Future Lab Space10, IDEO CoLab, and Gensler, and it continues to curry favor from a growing number of organizations and cities.

Concepts like the "15-Minute City" are on the minds of many planners around the world, including Toronto and Paris.

2. Data-first

Our streets have been governed by anecdotes instead of analysis. - Janette Sadik-Kahn, Former NYC DOT Commissioner

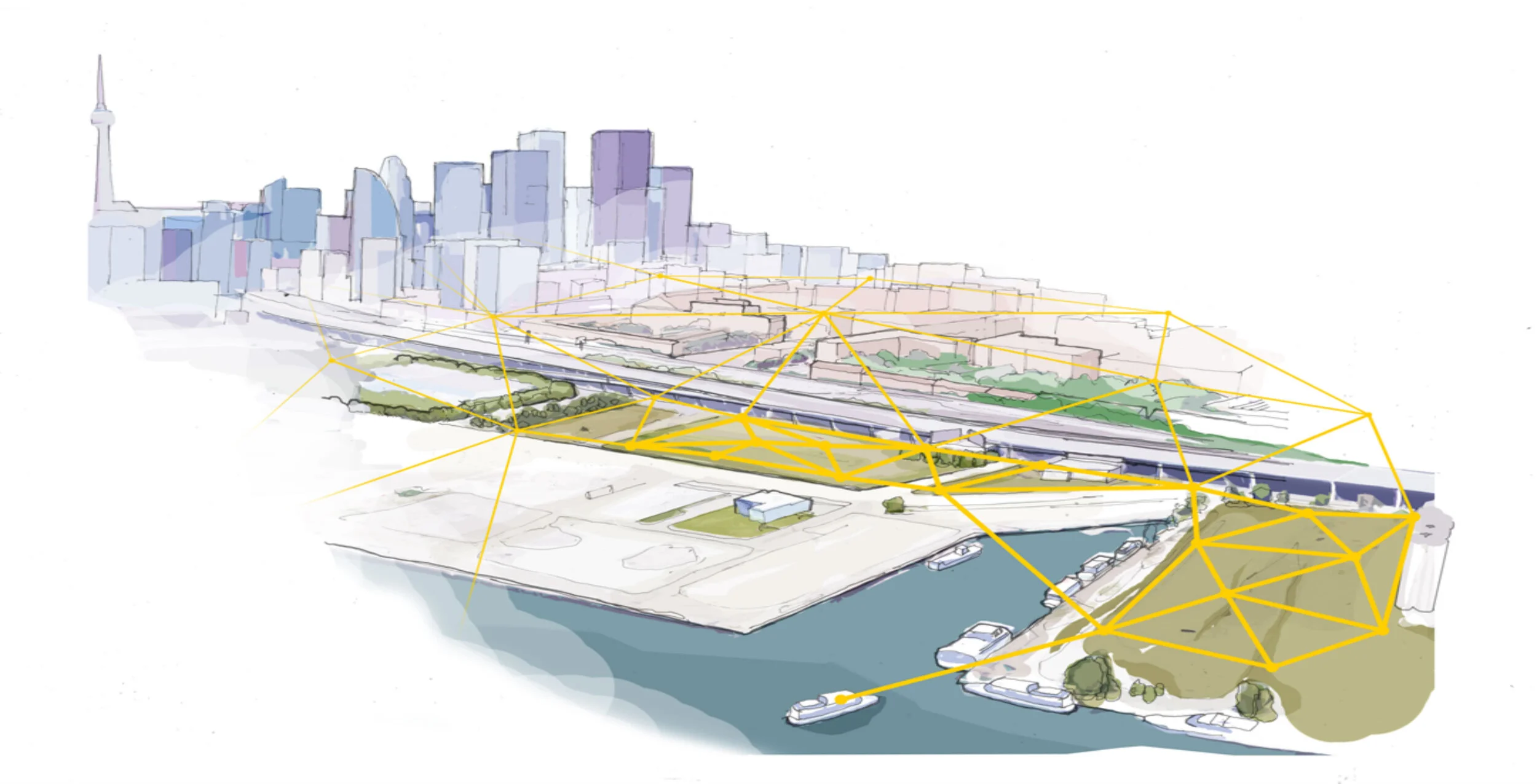

The data-first approach emphasizes generation, collection, and analysis in an attempt to optimize infrastructure and enhance the core experiences of a population from transit to commerce. And this approach is unsurprisingly supported by technologists, agencies, and global consulting firms including, most famously, Sidewalk Labs and its subsidiaries, McKinsey & Company, General Electric, and special projects like New Cities at Y Combinator.

Not all urban technology initiatives are created equal. While some projects focus on the data, others focus on implementing a growing list of sustainable solutions, including modular manufacturing, renewable energy sources, 3D printing, and self-driving cars.

3. Policy-first

Part of Copenhagen's success is that they've had a very incremental approach to the urban development instead of having a giant master plan, they've tested and tried out different solutions. - Helle Søholt, CEO at Gehl

Policy and governance are the communication layer between innovators and citizens, playing the difficult role of listener, advocate, and protector. Policy is often cast in negative light — slow-moving, conservative thinking, with rolls of red tape.

Especially in the US, where cities are locally funded, it's difficult to make broad decisions that meet the demands of millions of people, while protecting privacy, addressing inequities, reducing crime, improving safety, and the list goes on.

But since the beginning of the modern city, systems from the Model Cities Program to the compact city have aimed to make cities productive, creative, and competitive, while addressing the rising challenges from a growing population in a way that's good for the economy.

Interdependency

After studying each, it became clear that these weren't competing approaches, but an interdependent network of functions. In the global fight against climate change, we need to fully understand the values in each approach and apply equal amounts of social study, technology, and policy at scale.

Anthropology and social science uncover the questions that we need to answer with technology. Technology enhances our understanding of human behaviors through quantifiable data. Data improves our ability to communicate effectively through words, laws, and policy. Policy and planning enhance the lives of people in our cities.

Cities are never finished. Like good tech products, they require regular maintenance, periodic refactoring, and new features to meet the needs of a growing population. The truth of master-planned cities like Quayside, Songdo, or Dubai is that they leave little room for change — a waterfall approach to urban development. But cities are constantly in flux and planners, technologists, and policymakers need to adopt an agile approach to learn and adapt to changing behaviors and needs.